During the Second World War, the United States was pumping out weapons, aircraft, and tanks at an absolutely astonishing rate. The production of military vehicles and equipment was industrialized like never before, and with luck, never will be again. But even still, soldiers overseas would occasionally find themselves in unique situations that required hardware that the factories back at home couldn’t provide them with.

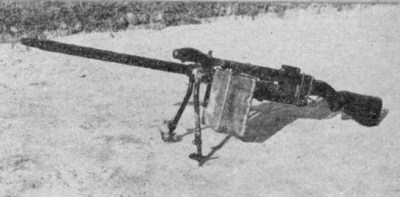

Which is precisely how a few United States Marines designed and built the “Stinger” light machine gun (LMG) during the lead-up to the invasion of Iwo Jima in 1945. The Stinger was a Browning .30 caliber AN/M2, salvaged from a crashed or otherwise inoperable aircraft, that was modified for use by infantry. It was somewhat ungainly, and as it was designed to be cooled by the air flowing past it while in flight, had a tendency to overheat quickly. But even with those shortcomings it was an absolutely devastating weapon; with a rate of fire at least twice that of the standard Browning machine guns the Marines had access to at the time.

Six Stingers were produced, and at least on a Battalion level, were officially approved for use in combat. After seeing how successful the weapon was during the invasion of Iwo Jima, there was even some talk of putting the Stinger into larger scale production and distributing them. But the war ended before such a plan could be put into place.

As such, the Stinger is an exceedingly rare example of a field modified weapon that was not only produced in significant numbers, but officially recognized and even considered for adoption by the military. But the story of this hacked machine gun actually started years earlier and thousands of kilometers away, as Allied forces battled for control of the Solomon Islands.

Battlefield Improvisation

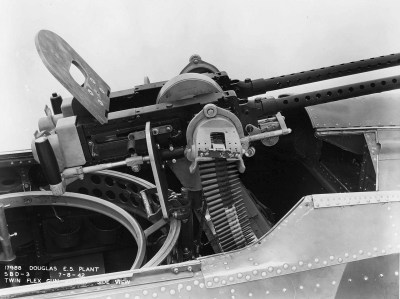

Looking for any possible advantage over a tenacious and entrenched adversary, the fact that soldiers would attempt to re-purpose the AN/M2 for infantry use is hardly a surprise. After all, there would have been no shortage of these high-performance weapons. The AN/M2 was fitted as defensive armament on many US Navy aircraft used in the Pacific theater, such as the SBD Dauntless, PBY Catalina, and Grumman Avenger. Each time one of these aircraft became too damaged to fly, several AN/M2s would become available.

They weapon also had some very compelling features. Since it was developed for use in planes, it was built to be as light as possible while still delivering the high rate of fire necessary for air-to-air combat. Compared to the standard M1919 Browning in use by infantry, the AN/M2 would have seemed like a considerable upgrade.

Unfortunately, while the weapon was light enough to easily carry, it was impractical for a soldier to actually operate reliably in its standard configuration. Never intended to be used outside of an aircraft’s defensive turret, the AN/M2 didn’t have it own sights, a stock, or even a traditional trigger. It had all of the functional components, but none of the features which would allow a person to operate it.

But this didn’t stop Private William “Bill” Colby from pushing one into service while defending Bougainville island in 1943. By hastily attaching a bipod to the front of the AN/M2, he was able to rig the weapon up well enough to provide fire from a defensive position. The additional firepower allowed Colby to successfully repel a surprise Japanese assault, proving that the concept had enough merit to warrant further development.

Preparing for the Invasion

A year later, Sergeant Milan Grevich and Private First Class John Lyttle came up with their own take on the AN/M2 modification. While Private Colby’s addition of a bipod allowed the weapon to be fired from a stationary position, the Marines needed something they could take with them as they advanced from Iwo Jima’s beaches and moved deeper into the island. For their purposes, the AN/M2 would need to be far more mobile, and potentially even usable by a single soldier from a standing position.

Spare stocks for the M1 Garand rifle were cut down to size, hollowed out to accept the unique shape of the machine gun’s rear buffer tube, and bolted to the back of the gun. A trigger assembly was fashioned from scraps of sheet metal, and an adapter was fabricated so the bipod and carrying handle from the far smaller Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) could be fitted.

Simplistic front and rear sights were also fashioned (or in some cases, taken from a BAR) so the operator would have an idea of where their shots would land. But as the Stinger was meant to be used as a suppressive weapon in relatively close quarters, pinpoint accuracy was never really the goal.

The Stinger was born, and just in time. Supposedly the finishing touches were still being made on the guns even as the Marines sailed towards Iwo Jima. Gervich himself carried one of the six weapons into battle, four were distributed among the Company’s rifle platoons, and the last one was given to Corporal Tony Stein.

Legend of the Stinger

As Corporal Stein wasn’t from the same Company as Gervich or Lyttle, there’s some debate as to why he received a Stinger of his own. But as a machinist by trade, it’s possible that he assisted in the assembly of the weapons with the understanding he would be given one once they reached Iwo Jima. In any event, the exploits of Corporal Stein and his Stinger were immortalized in his posthumous Medal of Honor citation:

The first man of his unit to be on station after hitting the beach in the initial assault, Cpl. Stein, armed with a personally improvised aircraft-type weapon, provided rapid covering fire as the remainder of his platoon attempted to move into position.

….

Cool and courageous under the merciless hail of exploding shells and bullets which fell on all sides, he continued to deliver the fire of his skillfully improvised weapon at a tremendous rate of speed which rapidly exhausted his ammunition.

While the Stinger moniker itself was perhaps deemed inappropriate for inclusion in a formal citation, the fact that the weapon and its improvised nature was specifically mentioned multiple times speaks to how effective it was during the battle. Had the war continued much longer, it seems almost a certainty that more Stingers (officially sanctioned or not) would have been produced as soldiers heard accounts of how they performed on Iwo Jima.

A Brief Moment in Time

Despite the success of the Stinger at Iwo Jima, the story stops here. Six months after American forces raised the flag on Mount Suribachi, Emperor Hirohito officially announced that Japan would agree to the unconditional surrender outlined in the Potsdam Declaration.

Whatever interest there had been in mass producing the Stinger, or an LMG like it, the end of the war made it unnecessary. Like many of the other fearsome weapons that were proposed or tested during the the last throes of the Second World War, it was deemed excessive in the post-war era.

So where are the Stingers now? Nobody actually knows. Since they were built out of scrap parts, they wouldn’t have appeared on any official manifest. Once the war ended, weapons and equipment were often unceremoniously discarded. It’s entirely possible they never left Iwo Jima, and ended up buried under the island’s black sands. Or if they did get removed, they could have been dumped in the ocean along with all the other wartime hardware which suddenly became more of a burden than an asset. There may even be a Stinger collecting dust out there in someone’s attic; part of a trove of souvenirs that a stoic Marine brought home from the war, now dutifully stored by his grandchildren or great-grandchildren.

While the Stingers themselves may be lost, the story of the men who built them continues on. More than 75 years after a few enterprising young Marines decided to see if they could cobble together a machine gun more powerful than anything in their Government-sanctioned inventory, one can’t help but be inspired by their ingenuity as they prepared for what they knew might be the last days of their lives.

No comments:

Post a Comment