An enduring memory for most who used the 8-bit home computers of the early 1980s is the use of cassette tapes for program storage. Only the extremely well-heeled could afford a disk drive, so if you didn’t fancy the idea of waiting an eternity for your code to load then you were out of luck. If you had a Sinclair Spectrum though, by 1983 you had another option in the form of the unique Sinclair ZX Microdrive.

This was a format developed in-house by Sinclair Research that was essentially a miniaturized version of the endless-loop tape carts which had appeared as 8-track Hi-Fi cartridges in the previous decade, and promised lightning fast load times of within a few seconds along with a relatively huge storage capacity of over 80 kB. Sinclair owners could take their place alongside the Big Boys of the home computer world, and they could do so without breaking the bank too much.

When 80 kB Of Storage Was A Big Deal

As a traveler returning from a continental hacker camp the UK government requires me to sit out two weeks quarantine due to the pandemic, which I’m doing as the guest of Claire, a friend of mine who also happens to be a fount of knowledge on and prolific collector of 8-bit Sinclair hardware and software. Idly chatting about the Microdrive, she bought out examples of not only some of the drives and software, but also the interface system and an original boxed Microdrive kit. This gives me the opportunity to examine and tear down the system, and provide a fascinating insight for readers into this most unusual of peripherals.

Picking up a Microdrive, it’s a unit about 80 mm by 90 mm by 50 mm weighing just under 200 g, and it follows the same Rich Dickinson styling cues as the original rubber-key Spectrum. On the front is an opening about 32 mm by 7 mm for the Microdrive cartridges, and on each side at the rear is a 14-way PCB edge connector for connecting to the Spectrum and daisy-chaining to another Microdrive via a custom serial bus over supplied ribbon cables and connectors. A maximum of eight drives could be connected in this way.

The Spectrum was an amazing machine for its price in the early 1980s, but this was achieved at the expense of very little in the way of built-in hardware interfaces beyond its video and cassette ports. On its rear was an edge connector that essentially exposed the Z80’s various buses, , leaving any further interfaces to be connected via expansion modules. A typical Spectrum owner would probably own a Kempston joystick adapter in this manner, to name the most obvious example. A Spectrum certainly didn’t come with a Microdrive connector, so the Microdrive had its own interface. The Sinclair ZX Interface 1 was a wedge-shaped unit that engaged with the edge connector on the Spectrum and screwed to the bottom of the computer, providing the Microdrive interface, an RS-232 serial port, a simple LAN interface that used 3.5 mm jack connectors, and a replication of the Sinclair edge connector into which further interfaces could be plugged. This interface contained a ROM that mapped itself over the Spectrum’s internal ROM, which as we noted when the prototype Spectrum emerged at the Centre for Computing History in Cambridge, was famously shipped unfinished and with some of its intended capabilities unimplemented.

Let The Teardown Commence!

It’s interesting to talk about the hardware, but of course, this is Hackaday. You don’t just want to see it, you want to see how it works. It’s time for a teardown, which we’ll start by opening up the Microdrive unit itself. Just like the Spectrum, the top of the unit is covered by a stuck-on black aluminium sheet bearing the iconic Spectrum logo, this has to be carefully teased away against the remaining force of 1980s adhesive to reveal the two screws securing the top half of the case. As with the Spectrum it’s difficult to do this without bending the aluminium, so some finesse is required.

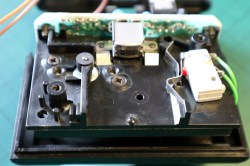

Lifting the top half clear and disengaging the drive LED, the mechanism and board come into view. Immediately the seasoned reader will notice that resemblance to the much larger 8-track audio cartridges, and though this is not a derivative of that system it works in a very similar way. The mechanism itself is extremely simple, on the right is a microswitch to sense when a cartridge has its write-protect tab removed and on the left is the motor shaft with a capstan roller. At the business end of the cartridge is a tape head that looks very similar to that you might find in a cassette deck but with narrower tape guides.

There are two PCBs, on the back of the tape head is one holding a 24-pin custom ULA (Uncommitted Logic Array, in effect a 1970s precursor to CPLDs and thus FPGAs) that selects and operates the drive, and another attached to the bottom half of the case that holds the two interface connectors and motor switching electronics.

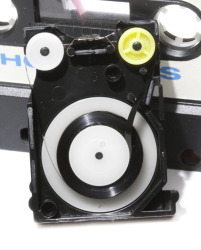

The cartridges are 43 mm by 7 mm by 30 mm, containing 5 metres of 1.9 mm self-lubricating magnetic tape in a continuous loop. I don’t blame Clare for not letting me lever open one of her vintage cartridges, but thankfully Wikipedia supplies us with a picture of a cartridge with the top off. Immediately the resemblance to the 8-track cartridges becomes apparent, the capstan roller may be to one side but the same loop of tape feeds back into the center of the single reel.

The ZX microdrive manual optimistically claims that each cartridge could hold 100 kB of data, but the reality was that they held about 85 kB rising to over 90 kB once they had stretched a little with some use. It’s fair to say that they weren’t the most reliable of media, with the tape eventually stretching to the point at which it could no longer be read and even the Sinclair manual advising backups of frequently used tapes.

The final component of the system to receive the teardown treatment is the Interface 1 itself. Unusually for a Sinclair product it doesn’t have any screws hidden under rubber feet, so aside from a delicate maneuver to detach the top of the case from the Spectrum edge connector it’s an easy teardown. Inside are three chips, a Texas Instruments ROM, a General Instrument ULA rather than the Ferranti item used in the Spectrum itself, and a bit of 74 logic. The ULA contains all the circuitry aside from discretes for driving the serial buses for RS-232, Microdrive, and Network. Sinclair ULAs are notorious for overheating and cooking themselves, and this is one of the most vulnerable. The interface here can’t have been used much because it hasn’t been fitted with a ULA heatsink and there are no heat marks in the case or around it.

A last word in this teardown should go to the manual, a characteristically well-written slim volume which gives an insight into the system and how it integrated into the BASIC interpreter. The networking ability is particularly fascinating as it was rare to see it in use, it relied on each Spectrum in the network issuing a command to assign itself a number upon start-up because there was no Flash or similar memory onboard. This would have been incorporated to target the schools market as a competitor to Acorn’s Econet, it’s not surprising to see why the BBC Micro won the Government supported schools contract instead of the Sinclair machine.

Why Are We Not All Using Little Tape Cartridges For Storage?

From 2020 it’s fascinating to go back and examine this forgotten piece of computing technology, and take a look at a world in which a 100 kB storage medium that loaded in about 8 seconds rather than the many minutes a cassette would have done was such a big deal. It’s baffling that Interface 1 doesn’t incorporate a parallel printer interface because looking at the complete Spectrum system, it’s not too difficult to see it becoming an adequate home office productivity computer for its day and certainly for its price. Sinclair did sell their own thermal printer, but even the most starry-eyed Sinclair enthusiast would find it difficult to claim the ZX printer as anything but a novelty.

The truth is that like everything Sinclair it was a victim of Sir Clive’s legendary cost-cutting and ingenious ability to create the impossible out of unexpected components. The Microdrive was completely developed in-house at Sinclair, but perhaps it was just too little, too unreliable, and too late. The first Apple Macintosh with its proper floppy drive arrived in early 1984 as a contemporary of the ZX Microdrive, and though the little cartridges found their way into Sinclair’s ill-fated 16-bit machine the QL, the result was a commercial flop. There would be a Spectrum with a 3-inch floppy from Amstrad once they had bought Sinclair’s assets, but by then the Sinclair micros were marketed purely as games machines. It’s been an interesting teardown, but perhaps it’s best to leave with happy memories of 1984.

I am heavily indebted to Claire for the use of the hardware featured here. In case you are wondering, the photographs above show a variety of different components both working and non-functional, in particular the Microdrive unit subjected to the full teardown is one that has failed. We prefer not to unnecessarily harm retrocomputing hardware here at Hackaday.

No comments:

Post a Comment