Electric cars, as a concept, were once not dissimilar from the flying car. Promised to be a big thing in the future, but hopelessly impractical in the here and now. However, in the last ten years, they’ve become a very real thing, with market share growing year on year as new models bring greater range and faster charging times.

With their lower emissions output and ever-improving performance, one could be forgiven for thinking that traditional combustion engines are all but dead. Mazda would beg to differ – investing heavily in new technology to take the gasoline engine into the next decade and beyond.

The Best Of Both Worlds

The holy grail of efficient combustion engines lies not with petrol, but with diesel engines. They routinely hit thermal efficiencies of over 40%, compared to the typical automotive gasoline engine which comes in closer to just 20%. This all comes down to the low volatility of diesel fuel. This enables diesel engines to run at very lean air/fuel ratios and incredibly high compression ratios, without the mixture prematurely detonating and damaging the engine or wasting power. It also enables the use of compression ignition, where the rising pressures inside the cylinder ignite the air/fuel mixture almost instantaneously, all at once.

Petrol engines, in comparison, have to carefully keep their air/fuel ratio much richer, from the stoichiometric level of 14:1, up to 9:1 under some conditions. This is to ensure the fuel doesn’t detonate instead of burning smoothly in a controlled manner. A sparkplug must be used to initiate ignition, with the flame front slowly moving through the mixture versus the instantaneous nature of compression ignition. Gas engines also run at much lower compression ratios – with a maximum of 14:1 seen in practice. Other factors also play a role, but mixture and compression ratio are the primary reasons diesel has such an advantage over gasoline in the efficiency stakes.

Over the years, many manufacturers have attempted to get gasoline engines to operate under compression ignition conditions. While several manufacturers have been able to make this work at low-RPM, low-load conditions. Under harder driving, the higher compression ratios required simply cause the air/fuel mixture to detonate, damaging the engine.

An Incredibly Complex Solution

Despite the difficulties, Mazda managed to build a production-ready compression-ignition gasoline engine, by the name of Skyactiv-X. Unlike previous attempts, it includes a spark plug in a creative hack that they call Spark Controlled Compression Ignition, or SPCCI, as explained in this excellent video by Alex On Autos.

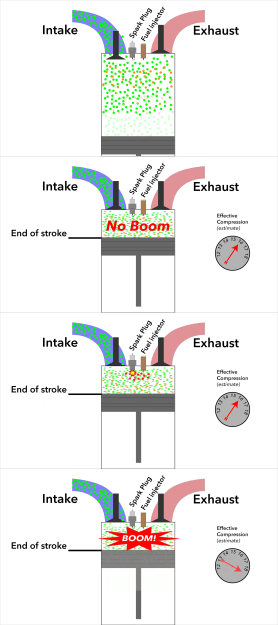

When running in this mode, the engine runs an incredibly lean air fuel mixture, on the order of 29:1 – so lean, even the engine’s high compression ratio of 16:1 won’t cause the mixture to combust. When the piston is reaching the top of the compression stroke, a small amount of extra fuel is injected, next to the spark plug. This localized richer mixture is ignited by the spark plug, with the combustion causing an increase of pressure in the cylinder. This added pressure then causes the rest of the mixture to undergo compression ignition. The result is a gasoline engine that can run at a higher compression ratio with a leaner air-fuel mixture than is traditionally possible. The target ratio is so lean that a low-pressure supercharger is used as a pump to supply more air to the combustion chamber.

The SPCCI regime is incredibly efficient, but when high power is required, it makes more sense to run the engine in a typical spark-ignition mode. With a compression ratio of 16:1, however, this would normally be difficult to achieve without detonation. However, modern variable valve timing enables the engine to leave the intake valve open during part of the compression stroke when operating in spark ignition mode. This reduces the engine’s effective compression ratio, allowing it to drop to a point suitable for traditional spark-ignition operation. This allows the engine to smoothly transition between SPCCI and conventional operation, something other manufacturers have thus far failed to achieve.

All this should add up to an engine that makes gains in efficiency, as well as power and torque. Mazda claims a fuel economy improvement of anywhere from 20 to 30% over their previous engines, and 30% more torque. Sadly, the data we’ve seen doesn’t entirely bear this out.

Looking at actual peak figures, the real numbers seem a touch underwhelming. Comparing the 2.0L Skyactiv-X to the previous 2.0L Skyactiv-G, we see a gain of just 12% in peak torque and 14% in peak power. However, this doesn’t take into account performance across the RPM band, and it’s possible that torque gains are much larger in the lower RPM range. As far as fuel economy is concerned, a 3-hour real world test didn’t show a whole lot of difference between the Skyactiv-X and the previous Skyactiv-G. Take into account that the Skyactiv-X also packs a mild hybrid system, and this is fairly disappointing. We’d like to look at this comparison again when the technology is a little more mature, but it’s a concerning result to say the least.

Of course, The sheer complexity of what Mazda has achieved should not be understated. Producing a production-ready, mass produced engine that can smoothly transition between compression ignition modes and regular spark ignition requires the combination of a swathe of technologies, from advanced computer engine controls, to direct injection and variable valve timing. The investment required in research and development to complete such a project is immense; the fact that no other automaker has achieved the feat should indicate the level of difficulty in mastering gasoline compression ignition.

It’s All About Return on Investment

Despite strong holds on some unique markets like Australia, Mazda remains one of the smaller automakers on the world stage. In vehicles produced, they ranked just 17th in the world, delivering 1.6 million vehicles in 2017. Unlike many other manufacturers, they are not part of a larger consortium, standing largely alone in a field dominated by heavy hitters like Toyota, Fiat-Chrysler, and Nissan-Renault-Mitsubishi. This makes their achievement all the more surprising, given the investment required and the resources available to this David amongst Goliaths.

It raises some eyebrows that Mazda has dedicated so many resources to the ongoing development of the gasoline engine, with many betting on an unstoppable wave of electric vehicles taking over market share in years to come. Other major players like Mercedes have already made moves to end development of gasoline engines. On top of this, with some cities looking to ban fossil fuel vehicles entirely in years to come, one wonders how much Mazda will be able to recoup the development cost over the next decade. Mazda’s own projections state that gasoline engines will still power 85% of all cars in 2035, but the more important figure is the proportion of new sales held by gasoline powered vehicles. BloombergNEF’s modelling expects to see electric cars take a 28% share of new car sales by 2030, so it seems there will still be plenty of time left for Mazda to cash in. It also serves as a useful gap-filler while the company begins a transition towards electric technology.

However, if SPCCI technology is to do well in the marketplace, it will have to make good on its lofty claims. While the new engine certainly packs better power and torque, it hasn’t yet shown a meaningful increase in fuel economy which is supposed to be one of its major benefits. And no matter how new and fancy it is, it can’t compete in the shiny, futuristic stakes with all-electric vehicles. Similar to Mazda’s prior experiments with Miller cycle engines in the 1990s, we suspect this may be more of an interesting blip than a game-changer for the gasoline engine. As always, time will tell.

No comments:

Post a Comment