By pretty much any metric you care to use, 2020 has been an unforgettable year. Usually that would be a positive thing, but this time around it’s a bit more complicated. The global pandemic, unprecedented in modern times, impacted the way we work, learn, and gather. Some will look back on their time in lockdown as productive, if a bit lonely. Other’s have had their entire way of life uprooted, with no indication as to when or if things will ever return to normal. Whatever “normal” is at this point.

But even in the face of such adversity, there have been bright spots for our community. With traditional gatherings out of the question, many long-running tech conferences moved over to a virtual format that allowed a larger and more diverse array of presenters and attendees than would have been possible in the past. We also saw hackers and makers all over the planet devote their skills and tools to the production of personal protective equipment (PPE). In a turn of events few could have predicted, the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic helped demonstrate the validity of hyperlocal manufacturing in a way that’s never happened before.

For better or for worse, most of us will associate 2020 with COVID-19 for the rest of our lives. Really, how could we not? But over these last twelve months we’ve borne witness to plenty of stories that are just as deserving of a spot in our collective memories. As we approach the twilight hours of this most ponderous year, let’s take a look back at some of the most interesting themes that touched our little corner of the tech world this year.

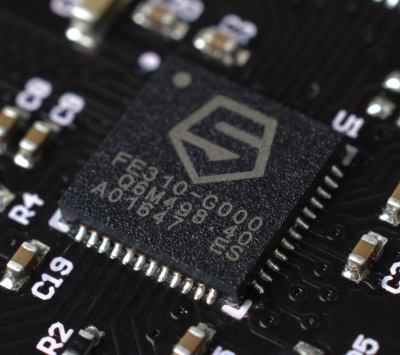

RISC-V Comes Alive

Like many of you, we’ve had our eyes on the RISC-V open standard instruction set architecture (ISA) for awhile now. Started in 2010 as a project to create an easy to understand ISA for academic purposes, it wasn’t long until major players in the hardware world came sniffing around. The simplified nature of RISC-V that makes it easy to teach naturally also makes it easy to implement in the real-world. Even better, its free. Manufacturers can build chips using RISC-V without having to pay the exorbitant licensing fees that go along with more traditional architectures, and as everything in our lives gets “smarter” and the demand for various chips gets greater, that’s a very compelling concept.

But up until this point, it’s mainly been a lot of talk. Sure we had a pair of RISC-V CPUs running inside the FPGA of the 2019 Hackaday Supercon Badge, but that’s because of an amazing badge team led by [Sprite_tm] who are cool like that. Trying to find commercial hardware running the open ISA has traditionally been quite a bit harder. But in 2020 we’ve finally started to see some substantial movement towards bringing this exciting architecture into the mainstream.

But up until this point, it’s mainly been a lot of talk. Sure we had a pair of RISC-V CPUs running inside the FPGA of the 2019 Hackaday Supercon Badge, but that’s because of an amazing badge team led by [Sprite_tm] who are cool like that. Trying to find commercial hardware running the open ISA has traditionally been quite a bit harder. But in 2020 we’ve finally started to see some substantial movement towards bringing this exciting architecture into the mainstream.

Just last month we brought you word of the ESP32-C3, a new member in the exceptionally popular WiFi-enabled microcontroller family that ditches the Tensilica core for RISC-V. While the official position of Espressif is that the change to a new core won’t have much impact on the end-user, the widespread adoption of these chips in consumer electronics scene (not to mention the hacker scene) makes this a pretty big deal.

Around the same time, Bouffalo Labs introduced the BL602. This combination WiFi and Bluetooth chipset is based on a RISC-V core, and hoping it would pave the way towards blob-free wireless support on their future devices, PINE64 kicked off a community effort to reverse engineer it. It would have been nice if Bouffalo was a bit more forthcoming with the details, but it took awhile before the hacker community was able to fully unlock the ESP8266 and we saw how that turned out.

Hopefully chips like these can become early success stories that inspire other companies to finally get some RISC-V silicon in production. It’s too early to say if 2021 will be “The Year of RISC-V”, but it seems like it might finally be close at hand. Then again, we thought the same thing in 2018.

Lots of Legged Bots

Homebrew robotics projects are a good way to get a sense for what’s popular in the world of hobby electronics, as they often represent the state-of-the-art in terms of whats available to the average hacker at the time. A few years ago, driven by the development of cheap MEMS accelerometers, it seemed like everyone was building self balancing robots. So what was big in 2020? This year we noticed a considerable uptick in quadruped walkers, many clearly inspired by the animal-like creations of Boston Dynamics.

So what’s been the enabling technology that’s led to all of these four legged robots? From the specimens we’ve seen, we can identify a few common traits. In almost all cases they make extensive use of 3D printed structures, are bristling with servos, dotted with sensors, and feature a relatively beefy onboard computer to figure out all the kinematics. Of course, none of this is particularly new. But the relative cost of all of these elements, and the ancillary components to tie them all together, have never been cheaper.

But it’s more than just the hardware. Incredible projects like OpenDog really opened up the floodgates, and redefined what was possible on a hobbyist budget. From there, the knowledge started to spread and clever folks figured out how to distill the core concepts into ever cheaper implementations. Thanks to most of these builds being open source, each new one adds a little more to the pool of information available to the next person who wants to take on the challenge.

Naturally these wobbly hacker creations are a far cry from the almost frighteningly agile robots that Boston Dynamics began selling in 2020, but these are still early days. Just a few years ago, many would have doubted you could even build such a thing as an individual.

Designing Open Ventilators

Early in the pandemic, many hospitals found ventilators to be in woefully short supply. In the United States alone it was estimated as many as one million of the life-saving devices could be required, but even with the federal government’s emergency stockpile factored in, there were at most 200,000 of them available among the country’s various healthcare facilities. Heavily encumbered by patents and manufactured by only a handful of companies, there were grave concerns about scaling up traditional production to meet the potential demand.

In response, we saw a huge push towards developing an open source ventilator that was quick and inexpensive to manufacture. Hobbyists and professionals alike started pitching their ideas, ranging from relatively simple mechanisms for motorizing manually operated resuscitators to unlocking advanced functionality in commercially manufactured CPAP machines.

As the scale of the problem became clear, bigger players started to join the fray. While it wasn’t technically released under an open source license, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory was willing to give their FDA-approved design out to any firm that had the means of building them.

Ultimately, the activation of the Defense Production Act allowed companies like General Motors, Ford, and General Electric to start producing either ventilator components or complete units at a phenomenal rate. In addition, less invasive ways to treat patients with COVID-19 were discovered, reducing the number of ventilators hospitals ended up needing.

Things thankfully never got bad enough that hackerspaces had to start churning out ventilators. However, a high point in all of this was seeing the community rally around PPE production of things like face shields and masks — leveraging small-scale manufacturing on a widespread basis until industrial supply chains moved enough to take up the slack. Bravo hackers!

Rise of the Cyberdeck

In his 1984 novel Neuromancer, William Gibson provides some exceptionally vague descriptions of customized “decks” that various characters use when they want to log into cyberspace. All he says is that they’re relatively portable, have a few blinking lights, and feature plenty of switches and keys. That’s all it took for readers’ imaginations to run wild, and with time, other artists co-opted the idea and put their own unique spin on it. But it took a couple decades before anyone tried to build one of these cyberdecks of their own.

It’s hard to say when it happened with any certainty. The first time one popped up here on Hackaday was in 2018, and while we wouldn’t say that’s an authoritative date, it seems unlikely such projects could have escaped our notice for too long. What we do know is that 2020 is when the idea really took off. In fact, approximately 70% of the cyberdecks we’ve ever written about have been built within the last twelve months.

Part of this uptick is surely due to the fact that many people found themselves with an unusual amount of free time this year. But at least some credit has to be given to Jay Doscher, who’s open source designs spawned dozens of known variants. Decks based on his concepts are built into a heavy-duty Pelican case, meaning even if you’re not terribly into the whole cyberpunk genre, it’s still a great way to put together a rugged mobile computer.

In truth, it’s still difficult to quantify what makes something a cyberdeck. Purists would demand it have the same virtual reality capabilities of the Gibson’s decks, but the technology simply isn’t there yet. After seeing so many notable examples in 2020, the one thing we can say for sure is that a good cyberdeck should be a reflection of its maker. It’s not enough to just be a funky portable computer, it should exemplify the skills and interests of the person who built it. Whether it has a painstakingly designed and fabricated frame, or uses a mixture of system architectures to maximize the machine’s performance in different scenarios, it’s the unique traits of these machines that make them special.

Reaching for the Stars

In 2020, there were so many interesting space stories that we started doing a recurring roundup article that allows us to cover several of them at a time. If we stopped to give each new mission, spacecraft, or discovery its own article, we’d have to change the name of the site. After years of stagnation, space exploration is once again a booming enterprise. We haven’t seen this sort of rapid progress since the Space Race of the 1960s, and considering many of us weren’t around to experience those days first-hand, it’s understandably a very exciting time.

NASA has a far-reaching plan to return humans to the Moon, and has officially started flying astronauts on commercial vehicles. Both international and commercial cooperation are a major part of NASA’s Moon ambitions, with companies like Blue Origin and SpaceX already being awarded contracts to build the various spacecraft and rockets that would make up the overall Artemis program.

NASA has a far-reaching plan to return humans to the Moon, and has officially started flying astronauts on commercial vehicles. Both international and commercial cooperation are a major part of NASA’s Moon ambitions, with companies like Blue Origin and SpaceX already being awarded contracts to build the various spacecraft and rockets that would make up the overall Artemis program.

So why has space suddenly become so popular again? Put simply, it’s cheaper than ever. SpaceX has made reusability a cornerstone of their operations, with almost all of their 2020 missions utilizing previously flown boosters. Other commercial launch providers are similarly investing in reusability, with Rocket Lab recently recovering their Electron booster for the first time. Earlier in the month SpaceX also conducted a dramatic test flight of their next-generation Starship vehicle which the company claims will eventually be even cheaper to fly than the Falcon 9.

This was also a banner year for sample return missions. In October, OSIRIS-REx became the first NASA spacecraft to collect a surface sample from an asteroid. On December 6th the Japanese Hayabusa2 delivered its own payload of soil and rock samples that were collected from the asteroid Ryugu in 2018. Just a few days later China made history by being the third country to successfully return a sample of lunar material to Earth; an important step towards their long term goals of landing human explorers on the Moon in the 2030s.

Unfortunately, not all the space news was positive in 2020. The scientific community was rocked by the heartbreaking collapse of the Arecibo Observatory. The loss of this unique radio telescope not only hinders our ability to conduct radar astronomy, but further limits humanity’s ability to detect potentially hazardous near-Earth objects. As disastrous as the loss of Arecibo was, the fact that there’s no guarantee it will ever be replaced is even worse.

Onward to 2021

This time last year we made some predictions for 2020, and while we didn’t anticipate the global pandemic that was about to hit us in a few months, the rest of it panned out pretty much as expected. The demand for electric vehicles has lead companies like Tesla to start investing in new battery technology, and though this year did see the Raspberry Pi 4 take on a few new forms, ARM SBCs in general seem to have plateaued a bit.

So where do we see things going in 2021? In addition to the new RISC-V hardware we’ve already talked about, expect to see more second-hand FPGAs to hit the market for pennies on the dollar. If you can find an obsolete piece of gear that uses an FPGA, there’s a good chance you can turn it into a budget development kit.

Machine learning is likely to get a boost thanks to increasingly cheap hardware from major players such as Google and NVIDIA. It’s hard to imagine 2021 will see anything cheaper than the $59 Jetson Nano 2 GB, but the fact that this affordable hardware is now hitting the mainstream should allow for higher adoption in the hacker and maker scene.

Special Thanks

The end of the year is always a good time to reflect on what really matters, but in 2020 it seems more important than ever. Everyone at Hackaday is extremely grateful to our readers and this community for sticking together even when there’s so much uncertainty in the world. We know it’s been tough going for a lot of folks, and the reality is that things may well get worse before they get better. It’s our sincere hope that through these troubled times and whatever lies ahead, that we’re able to inspire you to keep moving forward.

No comments:

Post a Comment