With the rise of usable electric cars in the marketplace, and markets around the world slowly phasing out the sale of fossil fuel cars, you could be forgiven for thinking that the age of the internal combustion engine is coming to an end. History is rarely so cut and dry, however, and new technologies aim to keep the combustion engine alive for some time yet.

One of the most interesting technologies in this area are hydrogen-burning combustion engines. In contrast to fuel cell technologies, which combine hydrogen with oxygen through special membranes in order to create electricity, these engines do it the old fashioned way – in flames. Toyota has recently been exploring the technology, and has announced a racecar sporting a three-cylinder hydrogen-burning engine will compete in this year’s Fuji Super TEC 24 Hour race.

Hydrogen Engines?

The benefit of a hydrogen-burning engine is that unlike burning fossil fuels, the emissions from burning hydrogen are remarkably clean. Burning hydrogen in pure oxygen produces only water as a byproduct. When burned in atmospheric air, the result is much the same, albeit with small amounts of nitrogen oxides produced. Thus, there’s great incentive to explore the substitution of existing transportation fuels with hydrogen. It’s a potential way to reduce pollution output while avoiding the hassles of long recharge times with battery electric technologies.

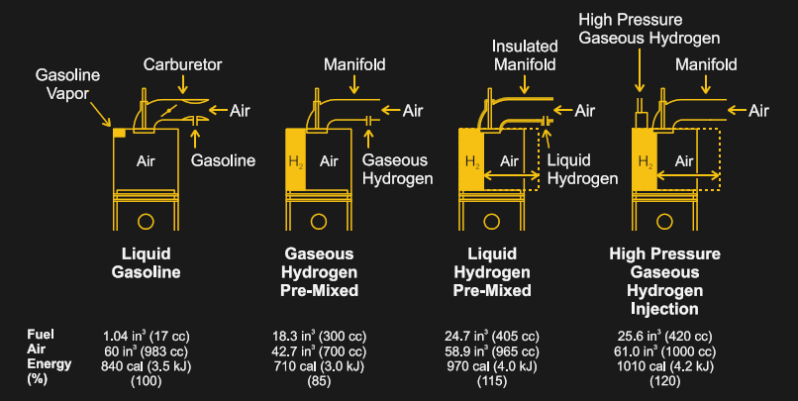

The basics of a hydrogen-burning combustion engine are largely the same as any gasoline engine out there. In fact, virtually any existing gasoline engine can be converted to run on hydrogen simply by replacing the fuel injectors with parts suitable for injecting hydrogen instead. However, due largely to the fact that a combustible mixture of hydrogen and air takes up more space in a cylinder that would otherwise be for air, power output would be reduced by 20-30% compared to the same engine burning gasoline, assuming the hydrogen is injected prior to intake valve closure.

However, measures can be taken to offset this. By designing engines to burn hydrogen from the outset, things like compression ratio, combustion chamber design, and injection methods can all be optimised to suit hydrogen fuel. For example, by using direct injection technology to squirt hydrogen into the combustion chamber after the intake valve is closed, power of a hydrogen engine can be increased significantly. This is due to the engine vacuum on the intake stroke pulling in 100% air, rather than 30% of the space being taken up by hydrogen in a stoichiometric mix.

There are still engineering problems that remain to be solved before hydrogen engines can go mainstream. There’s also the same chicken-and-egg distribution problem that affects fuel cell cars; it remains difficult for companies to sell hydrogen-powered vehicles in the absence of filling station infrastructure. There are also issues of crankcase ventilation, where gaseous hydrogen can ignite in the crankcase having slipped past the piston rings, as well as backfire issues in systems that premix the hydrogen gas in the intake. None of these problems are insurmountable, however, and solving them is more a case of routine engineering effort rather than blue-sky research.

It also bears noting that, while hydrogen-burning engines are far cleaner than their fossil-fuelled equivalents, and don’t emit any CO2, trace amounts of lubricant oils still sneak through the combustion process because no piston rings are perfect. Obviously, this is not a problem for hydrogen fuel cells.

Real-World Examples

Toyota’s racing entry will field a three-cylinder engine in a car based on the Toyota Corolla Sport, intending to compete in a 24-hour endurance race. There isn’t a whole lot more to go off, though a YouTube video on the hydrogen engine seems to imply that port injection, rather than direct injection, is being used. This is not surprising, because the racing entry is essentially a technology demonstrator to raise the profile of hydrogen cars, rather than an all-out effort to produce the highest possible power with a hydrogen engine.

Toyota aren’t the only company experimenting with the technology, however. Mazda’s efforts resulted in the RX-8 Hydrogen RE, sporting a duel-fuel Wankel engine capable of burning gasoline or hydrogen as required. A small number of these vehicles were leased out in various locations with suitable filling infrastructure.

BMW went as far as building a version of its 7-series luxury sedan complete with a 6.0 litre dual-fuel V-12 engine. The engine gave up some performance compared to the solely gasoline powered models, however, and was also only released in limited numbers from 2005 to 2007.

Earlier projects such as those from BMW and Mazda raised significant interest, but little genuine demand from the marketplace. High prices combined with rudimentary hydrogen storage technology, along with a near-total lack of infrastructure, meant that such cars weren’t a great proposition for the average driver.

While previous experiments with hydrogen combustion engines have fallen flat, the continual push to develop better hydrogen storage and filling stations, as well as better performing engines, may yet see it have some promise in the future. However, it will be an uphill battle against existing electric cars, which have a huge lead in the infrastructure race, as well as in hearts and minds.

No comments:

Post a Comment