Food poisoning is never a fun experience. Sometimes, if you’re lucky, you’ll bite into something bad and realize soon enough to spit it out. Other times, you’ll only realize your mistake much later. Once the tainted food gets far enough into the digestive system, it’s too late. Your only option is to strap in for the ride as the body voids the toxins or pathogens by every means available, perhaps for several consecutive days.

Proper food storage and preparation are the key ways we avoid food poisoning today. However, a new development could give us a further tool in the fight—with scientists finding a way to actively hunt down and destroy angry little pathogens before they can spoil a good meal.

Hunt Them Down

Food poisoning cases tend to boil down to two categories—those involving toxins, and those involving bacterial pathogens. In either case, affected food must be destroyed. Particularly in the latter case, as bacteria reproduce—even the tiniest contamination will quickly spiral in size.

However, new research published in Scientific Advances may have a solution to the problem of bacterial-based food poisoning. It involves using patches to deliver specially-crafted viruses to fight and kill the bacteria that would otherwise infect and sicken a human who eats the food. The patches are to be applied to the food itself—attacking and killing the bacteria before the food is eaten.

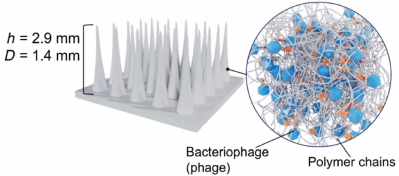

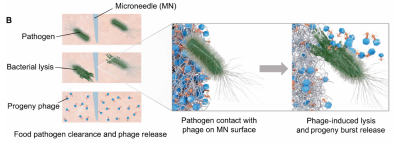

The viruses in question are bacteriophages—specifically, viruses that can infect bacteria and reproduce within them from its own genetic material. When a bacteriaphage virus comes into contact with certain bacteria, it breaches the cell’s wall, typically with a syringe-like motion in which the viral genetic material is injected into the cell. Once inside, the genetic material is processed by the bacteria and reproduces more phages that can then go on to infect further bacteria. In the specific case of lytic phages, the bacterial cells are quickly destroyed as the virus reproduces inside, spreading the new phages quickly and killing the original host.

Two bacteriophages were used in this research. The T7 phage was chosen for its ability to infect and kill Escherichia coli bacteria, which are a common foodborne pathogen. The S.enterica phage was in turn chosen as it readily infects and kills Salmonella enterica bacteria, which are similarly a common cause of food poisoning.

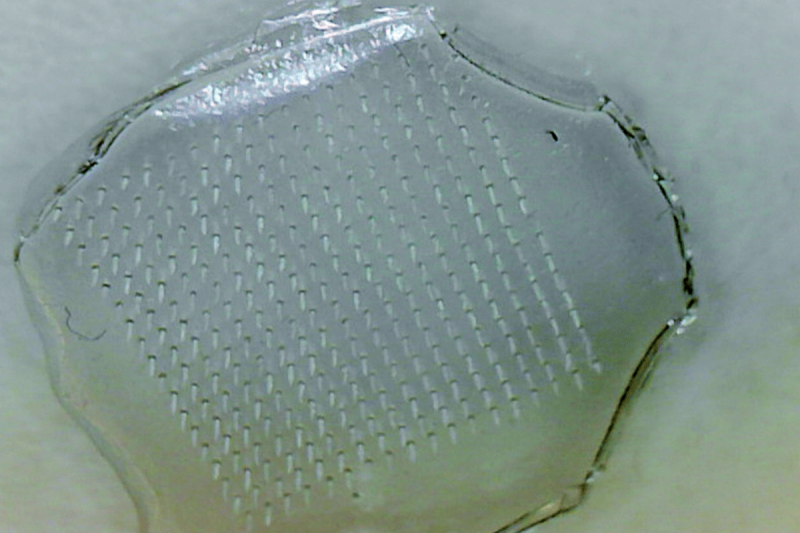

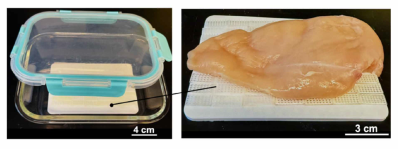

To get the phages into food items, the research team developed a novel “patch” delivery system. This involved creating patches out of food-compatible polymers that were covered in tiny microneedles that could penetrate the surface of common foods. Once the microneedles penetrate the food, passing bacteria would interact with the bacteriophages, producing more phages as they burst open and die. This has the effect of propagating phages further to other bacteria in the food. The most successful microneedle patches were crafted out of PMMA polymer, after researchers investigated a wide range of other materials including PVA, PDMS, and gelatin. The microneedles are dosed with bacteriophages by simply incorporating the bacteriophage solution with a PMMA solution prior to casting in molds.

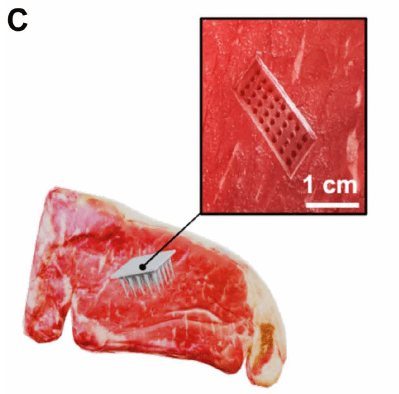

The patches proved effective in testing. One test involving contaminated cooked chicken saw 99.9% of E. coli bacteria wiped out in the sample. A similar test on raw beef saw a similar reduction of E.coli by 99%. These samples could effectively be considered decontaminated from the bacterial threat. The use of microneedles is key to the technique’s effectiveness. By penetrating up to a centimeter into the meat, it allows the bacteriophages to best get into contact with pathogens inside the food. In comparison, flat patches without needles performed less well, only reducing bacteria levels by three-quarters.

The research around using patches to deliver bacteriophages to food was only just published in October this year. However, the use of phages as a food safety measure actually goes back quite some time. The FDA first approved the use of bacteriophage products in 2006, initially for killing bacteria in ready-to-eat poultry and meat products. The same techniques can be applied to all sorts of foods, though use thus far has been limited. The US has actually been a leader in approving these food treatment methods; as a contrast, the European Union is yet to approve any use of bacteriophage products for food use.

As to whether these patches could enter wider use, that remains to be seen. There are some limitations with the technique. For one, it involves punching many small holes in food, which isn’t super attractive to those going to eat it later. There are also concerns about the effectiveness of phages in real-world use, and whether it would be practical to dose patches with a wide range of phages to counter the many strains of foodborne pathogens out there. It also depends on the perception of the tecnnology—we’d all rather eat food free of bacteria, but whether we want to eat food that is full of viruses is another thing entirely.

It will be a while before this technology reaches the mainstream food processing world, if it does at all. Regardless, the researchers can see a future where food packaging regularly includes a microneedle pad or membrane to take out any nasty bacteria before the product reaches the customer. That could promise to land better, safer food on our tables even if a few nasty bacteria did try to get involved in the action.

Featured image: microneedle array image from “Nanoparticle-infused-biodegradable-microneedles as drug-delivery systems: preparation and characterisation“.

No comments:

Post a Comment